Edward Woods, Past-President of the Institution of Civil Engineers, was born in the City of London, on 28th April 1814, the second son and ninth of twelve children of Samuel Woods and Lucy Webb. His father was a merchant residing and carrying on business in Lombard Street. After instruction by a governess Edward's education continued when he was 11 and went to Dr Cogan's school at Walthamstow.

When Dr Cogan retired, Edward Woods was placed at the school of Dr Schwabe, on Stanford Hill. Business was slack when Woods left school and so he could not be placed as a pupil at the Neath Abbey Iron Works of Joseph Price as soon as desired.

Instead of awaiting a definite appointment, Woods pursued studies in civil engineering, the profession to which he aspired, but without having access to the advantages for technical training expected nowadays. During that time he visited and spent some time with relatives resident in Liverpool, and was therefore introduced to friends connected with and interested in the Liverpool and Manchester Railway which then had recently been completed and opened for traffic. Through the kindness of a director and the treasurer of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, Woods was entrusted, under a four years' agreement at a small salary, with the supervision of 15 miles of the line from Liverpool to Newton le Willows, under John Dixon, who had just succeeded George Stephenson as chief engineer.

When Dixon became Chief Engineer, Woods was appointed one of his assistants, and took charge of the section from Liverpool to Newton-le-Willows, including the tunnel between Lime Street and Edge Hill, which was then under construction.

The duties assigned to this young engineer were to superintend the works, to look after the contractors for the permanent way, set out new works, pay the contractors, police, etc., along the line, and attend the fortnightly meetings of the Board of Directors. Woods was thus involved in development of railways from their very early days.

In 1836 Woods succeeded John Dixon as Chief Engineer to the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, with the additional charge of the mechanical department. One of the first practical insights he gained was the importance of laying rails on an elastic road-bed. In the first instance the line had been laid, during its construction in 1829, with wrought-iron fish-belly rails, costing £11 to £12 a ton, carried in chairs which were fixed in stone blocks in all the cuttings. Sleepers were only used on the embankments, in order to facilitate the repairs of the road and the raising of the line when the embankments settled. How firmly the mistaken belief in a rigid roadway was at first entertained may be gathered from the fact that, in making the Manchester and Bolton Railway, the rails were laid on solid stone walls only to be taken up later and relaid on sleepers.

Resistance to railway trains was another early subject of experimental investigation by Woods. To determine the mean value of 'railway constants', the British Association appointed in 1837 a committee, of which Woods was a member, together with Alexander Rennie, Sir John Macneill, Mr Locke, Dr Dionysius Lardner and Hardman Earle.

Their first experiments, reported by Dr Dionysius Lardner to the Newcastle meeting in August, 1838, were made in the same year by observing the known action of gravity upon trains of given weight descending given gradients. The resistance could then be correctly deduced when a uniform velocity had been attained. Analysis of the engine power was less satisfactory. In Woods' opinion, the information on the action of the steam in the cylinders was not sufficiently accurate. Moreover, apart from air resistance at the front of an engine one also had to consider the friction of the body of air carried along with the train. In July and August, 1839, a second series of experiments were made. These were reported to the British Association Meeting in 1841, by Dr Lardner and also by Woods, who had been largely instrumental in personally carrying out both series of trials (British Assoc. Report, 1841, p. 247).

On 30th January 1838, Mr Woods read a paper (Transactions ICE, vol. ii. p. 137, and Minutes of Proceedings ICE, vol. i, 1838, p. 3) on the locomotive engines on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. This paper gave, according to the report of the Council for 1840, some of the earliest and most accurate details on the actual working of locomotive engines, and seems to have been his first recorded connection with the Institution of Civil Engineers.

In 1843 he laid before the Liverpool Polytechnic Society a review of the circumstances which had affected the consumption of fuel in the locomotives of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway from the opening of the line to the end of 1843. That paper was published in 1844 and became a contribution to a new edition of Tredgold's 'Steam Engine' in 1850. Again in 1850, while still in Liverpool, he published a pamphlet giving his observations on the consumption of fuel and the evaporation of water in locomotive and other steam-engines, and mention of his personal knowledge of many facts connected with the history and development of the locomotive engine on the first field of its application to the transport of passengers and merchandise at high velocities - namely, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. In 1848 he also made a trial of burning anthracite instead of coke.

Woods remained with the Liverpool and Manchester Railway for 18 years until 1852, by which time the railway had been merged with the Grand Junction Railway. He remained in the service of the amalgamated companies to design and carry out the various works specially identified with the interests of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company. The principal of these was the Victoria Tunnel passing under the City of Liverpool for two miles.

Another work was the railway connecting the main line at Patricroft with the Liverpool and Bury Railway at Clifton, which was opened in January, 1850. Elected a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers on 7th April 1846, he became a member of its council in December 1869, and was president in 1886-7. His presidential address (Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. lxxxvii. 1) contains much information as to the early history of railways. In 1884 he was president of the Smeatonian Society of Civil Engineers.

The subject of the choice of the best fuel for locomotives occupied much of his attention. Trials had been made in 1852 of burning coal in locomotives, instead of coke, which till then had been universally employed. In 1853, in conjunction with William Prime Marshall, he presented three joint reports to the General Locomotive Committee of the London and North Western Railway, giving the results of experiments carried out with passenger and goods engines. The conclusion arrived at was that lighter and smaller engines worked the trains as well as larger and heavier ones, consuming the same amounts of water and coke when running with equal loads at equal speeds. In 1854 a further joint report was presented on the use of coal and on the whole the conclusion seems to have been unfavourable to coal. In his experience there was no fixed ratio between the evaporative power of fire-box surface and tube surface in locomotive boilers; and whatever the ratio might happen to be it had nothing to do with economy of fuel.

After the amalgamations with the Grand Junction and London and Birmingham Railways he took a separate office in Liverpool, combining private practice with the conduct of the works as above indicated. During this period he first became interested in works projected on the West Coast of South America. Already in 1849, Woods had been interested in connection with the Liverpool firm of Graham, Kelly & Co. in the superintendence of material required for construction of the Lima and Callao Railway.

At the close of the year 1853 he settled in London to broaden his practice and opened offices in Westminster. He became extensively engaged on the construction of various railways, waterworks, and gas works, including provision of all necessary equipment, machinery, and rolling stock. In addition to an extensive practice in England and some of its colonies, and the construction of the Bilbao River and Cantabrian Railway in the north of Spain, Woods was largely connected with engineering undertaking in the South American Republics. In some of his South American work he acted as consulting engineer for Wheelwright's projects and thus eventually became interested in Argentine railways.

From the time when the Santiago and Valparaiso Railway was constructed, he enjoyed the confidence of the Chilean Government and for 40 years was its consulting engineer. Woods also acted as consulting engineer for private undertakings in Chile: Wheelwright's Copiapó Railway; the Coquimbo, Carrizal, Tongoy, Chañaral, Antofagasta Railways and Nitrate Railways, and the line from the Port of Tocopilla to the nitrate grounds in Toco, on the River Loa, 55 miles in length, with its pier and station works at Tocopilla and its ofice at Toco for manufacture of nitrate.

From the year 1870 to 1877 he acted as consulting engineer to the Peruvian Government during the construction of railways extending from ports on the coast inwards to the western slopes of the Andes chain. These lines were built by Henry and John Meiggs. They consisted of the following railways: The Callao and Oroya, Arequipa and Puno, sections of the Transandine Railways; Chimbote and Huaraz, Iceliaca and Cuzco, Pacasmayo and Magdalena, Ylo and Moquegua, Etén and Ferrinape.

The iron piers at the respective termini of the Arequipa and Puno Railway, a pier of 700 metres in length at the port of Mollendo, constructed by Henry Meiggs, were designed by Woods, the materials being sent out from England under his specification and superintendence.

He had previously designed and constructed an iron pier projected by Wheelwright at the port of Pisco, extending 670 metres (2,200 feet) out to sea into deep water, to enable the large coasting steamers to come alongside to load and discharge. This was severely tested but not damaged by the great earthquake wave in the year 1868 which overwhelmed the port of Arica, throwing a Government warship on high and dry land half a mile from the coast.

Political changes after 1877 resulted in suspension of public works in Peru. By then Woods had already been engaged by Argentine railways.

On 23 May 1863, William Wheelwright had concluded his contract with the Argentine Government for the construction of the Central Argentine Railway, 246 miles in length, to connect the town of Córdoba with the port of Rosario on the River Paraná. A limited liability company was shortly afterwards formed in London to take over the concession and its rights, and Woods was appointed their engineer. Under a contract entered into with the firm of Brassey, Wythes, and Wheelwright, on the 11th May 1864, the works were commenced and the entire line was completed and opened for traffic on 18th May 1870. The son, Edward Harry Woods acted as resident engineer, under his father, for the whole of that period.

The Buenos Ayres and Ensenada Port Railway Company, to which Woods was appointed engineer, was formed in June 1872, to take over the interest of Ogilvie, Wythes, and Wheelwright, for the construction of a railway from Buenos Ayres to Boca de Riachuelo, Barracas, and Ensenada. This line was opened to the port of Ensenada in 1873, Arthur Edmund Shaw having acted under Woods during this period as resident engineer.

When in 1888 the Ensenada Port Company formed the Ensenada and South Coast Railway Company, Woods was appointed engineer of that new railway holding that post until his death. For the parent Ensenada & Port Company he designed in 1886 a new bridge over the Riachuelo following the requirements of 'uniform stress' first pointed out by Professor Callcott Reilly; and buffet cars built in 1891. Woods has also been connected with other Argentine undertakings as, for instance, director of the City of Buenos Ayres Tramways from inception in 1869 to his death, and the Buenos Ayres and Belgrano Gas Company, as engineer; and with the Rosario and Paraná Waterworks Companies, as consulting engineer. In the years 1870 to 1872 he acted for the Argentine Government as consulting engineer of the Andino Railway to Río Cuarto and of a bridge over the Río Tercero, earning a commission of 3 percent of the value of materials inspected by him and shipped from England. In the annual report of the Ministry of the Interior (May 1872) he was considered the most notable and honest person engaged in his kind of work.

Though the battle of the gauges in 1838, provoked by I K Brunel's adoption of 7 feet for the Great Western Railway, showed that the majority of the combatants sided with the present standard 4 feet 8½ inches gauge, Woods, however, seems to have held the opinion that the Irish gauge of 5 feet 3 inches, or the Indian gauge of 5 feet 6 inches, would have been preferable to either of the two then engrossing almost exclusive attention. His subsequent experience comprised six railway gauges - 5 feet 6 inches, 4 feet 8½ inches, 3 feet 9 inches, 3 feet 6 inches, 3 feet, and 2 feet 6 inches - besides tramways of still smaller gauge. In the Australian colony of Victoria, where the 5 feet 3 inches gauge had been adopted and carried out for 453 miles, it was contemplated in 1872 to introduce a 3 feet 6 inches gauge for 600 miles of new lines projected. Edward Woods, Sir Henry Tyler and Thomas Elliot Harrison, independently of one another, were requested by Mr Childers, then Agent-General for Victoria, to report on the proposal. All three agreed in recommending that the existing 5 feet 3 inches gauge should be adhered to for the new lines, rather than that a second and narrower gauge should be introduced. The Colonial Government followed their advice. The difference in cost Woods calculated would not have been more than £360 per mile in favour of the narrower gauge, against which would have had to be set the grievous disadvantages of a break of gauge. On the same grounds he was of the opinion that in India it would have been preferable if branch lines had been made on the same 5 feet 6 inches gauge as the main lines, regarding it as a fallacy to consider that the cost of a railway is proportional to the width of gauge.

Generally, indeed, it may be said that he looked upon break of gauge as essentially a retrograde movement. Nonetheless it did appear to him that a mistake had been originally made by the Indian Government in sanctioning lines equal and even superior to first-class English railways. In the United States, and in the republics of South America, he found that standard-gauge railways were constructed at less than half the cost of the Indian lines. Prior to 1873 he had made the Central Argentine Railway, of 5 feet 6 inches gauge for little over £7,000 per mile, including sidings, stations, rolling-stock, and rails of 62 lbs. per yard. Yet earlier, about 1859 he had to construct the Copiapó Extension Railway of 27 miles, from Pabellón to Chañarcillo, in Chile, under instructions that the line was to be worked by mules. Mule traction proving a failure, he then designed engines light enough for the rails of only 42 lbs. per yard. By his work in Chile and Peru, Woods had also many years' experience of working round curves of even as little as 4 chains radius (80 metres - 264 feet) with engines having a four-wheel leading bogie with transverse motion, and without flanges on the leading driving wheels. On the lines in South America so worked he had no instance of derailment at the ordinary speeds of 25 to 30 miles an hour.

At the Plymouth meeting of the British Association in 1877 Edward Woods was President of the Mechanical Section, to which he delivered an address on the Subject of 'Adequate Brake Power for Railway Trains'. Therein he reported the experiments he made himself, in conjunction with Colonel Inglis, RE, for the Royal Commission which had been appointed in 1874 to inquire into the causes of accidents on railways. The experiments had been made with eight systems of continuous brakes and from the results observed he drew up a list of thirteen conditions which he considered indispensable for a continuous brake for heavy fast trains.

Turning to another branch of engineering, Edward Woods was Consulting Engineer to the Bournemouth Gas and Water Company from its incorporation in 1863 up to the time of his death. For the Corporation of the City of London he conducted a series of observations with Joseph Quick and Son, in connection with the Water Bill of 1884, of which the principal object was to give householders the option of metering their consumption. In 1869, Woods became engineer to the Montevideo Waterworks, projected by Lezica, Lanús and Fynn. Frederick Newman acted as resident engineer to superintend the construction, and, when the waterworks were taken over by an English Company, Woods had acted for some years as the consulting engineer. In the design of metal buildings, one of his notable works in South America was the Market in Santiago de Chile designed in 1870 with the assistance, among others, of Charles Henry Driver.

In 1893 Woods was a director of the following companies:

Bilbao River and Cantabrian Railway

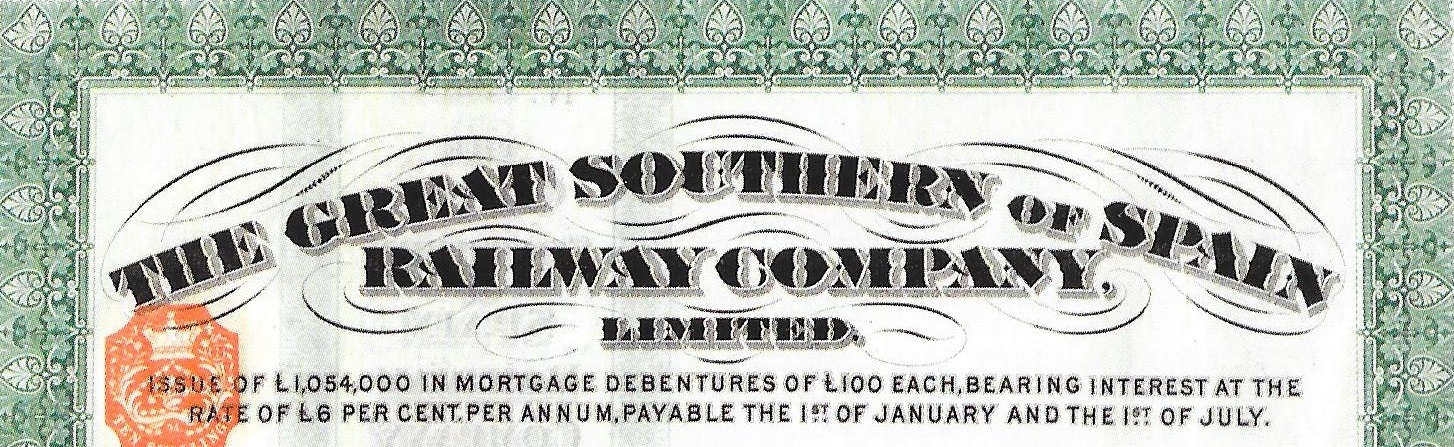

Great Southern of Spain Railway

Brush Electrical Engineering

Hong Kong & China Gas Co. (Chairman)

City of Buenos Ayres Tramways

New Imuris Mines

Colombo Gas & Water Co.

North West Argentine Railway (Chairman)

Seville Tramways Co. (Chairman).

He had resigned from the board of the North West Argentine Railway in 1894 but remained as trustee for the debenture stockholders. He and his son Harry had also been long-time shareholders in the Buenos Ayres Great Southern Railway.

From this sketch it will be seen that Edward Woods was an engineer of wide experience and large views, who, from the beginning of the railway industry, was always leading its progress. How much he enjoyed his work was witnessed when in July of 1902 he visited the Blagdon Waterworks, in Somerset. In that excursion, to which the Council of the Institution were invited by the engineer of the undertaking, Woods tramped about cheerily with the rest of the visitors over all the ground they had to traverse on foot for inspecting the work completed and in progress.

Edward Woods married Mary Dent on 5th October 1840, daughter of Thomas Goodman of Birmingham. They had three sons and two daughters. At their home on 45 Onslow Gardens, Kensington, London, they employed five servants in 1881. Edward Woods died at his residence, 45 Onslow Gardens, London, on 14th June 1903, and was buried at Chenies, Buckinghamshire.

Information taken from 'Who was who in Argentine Railways' by Sylvester Damus.