LEGAL PROBLEMS

See also the comments by Miguel Lloret Baldó in El Boletín

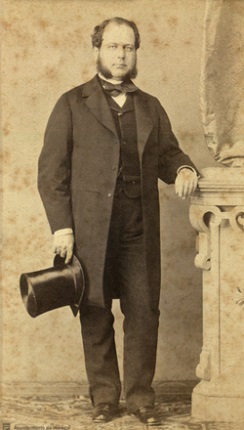

THE MARQUIS OF CASA-LORING

In the beginning The GSSR contracted Hett, Maylor & Co Ltd for the construction of

various sections, at a rate per kilometre, depending on the various

sections, and for their part, they contracted The Marquis of Casa-Loring ("Loring") to build this at a fixed price depending on the type of

work, this being the 53 kilometres between Lorca and Zurgena.

In the beginning The GSSR contracted Hett, Maylor & Co Ltd for the construction of

various sections, at a rate per kilometre, depending on the various

sections, and for their part, they contracted The Marquis of Casa-Loring ("Loring") to build this at a fixed price depending on the type of

work, this being the 53 kilometres between Lorca and Zurgena.

In the last weeks of 1890 there was a suspension of payments, resulting in the bankruptcy of Hett, Maylor & Co Ltd, the company that had suffered many disruptions and complaints from Loring and other smaller contractors who were now claiming against The GSSR. Due to the critical situation, the company decided to be represented in Spain by Mr Neil Kennedy, who had previously represented Hett, Maylor & Co Ltd and for that reason was conversant with the matters concerning the construction of this railway, and due to his character and position, could deal with the problems of construction as well as front himself against such a skilful man as Loring.

Hett, Maylor & Co Ltd had had many arguments with Loring, mainly over the quality of the construction work and short cuts he was doing. When Hett, Maylor declared bankrupty, they left owing Loring a significant sum of money. Loring saw (incorrectly) that The GSSR was responsible for the payments and took The GSSR to court in every borough where he had built the line. Loring also had many contacts in the 'establishment' putting Kennedy at a great disadvantage. This left The GSSR in great difficulty as the courts had frozen all activity on the Lorca to Zurgena section as well as materials. In addition, Loring had arranged for the illegal placement of obstructions on the Lorca - Zurgena line. This prevented The GSSR from receiving its subsidies for the completed section.

The company solicitors were getting nowhere, so Kennedy found the best solicitor in Spain, Mr Juan de la Cierva who had offices in Murcia. He considered the problem to actually be two problems - judicial (courts) and governance (blocked track).

We refer to Sr Lloret Baldo:

Thinking of sending a letter to the Governor against Loring requesting the removal of the obstacles was out of the question due to Loring's influence through his political son Sr Silvela who was once a minister, so Sr Cierva had to come up with an alternative solution. He had to hide the fact to the Governor that Loring was involved as the Governor had been told by the Government to give Loring all help necessary. So Sr Cierva said that they needed to pass the matter through the State Engineer due to the conflicting rules that were laid down in the law, and in this manner request the authorization for the opening of this section of track. For this he charged the representative of the Company in Madrid, Mr Henry Borrel, to communicate immediately by telegraph with Mr Kennedy and with great secrecy and urgency, Mr Kennedy and Sr Ciervo left for Almería.

On their arrival, they didn't waste time in visiting the Governor, Sr Ciervo saying with much indignance, that vandals (not Loring!) had placed obstacles on the track at Km X with the criminal intent to prevent the passage of the trains. The Governor was also indignant, but somewhat indecisive, but his wife, who was present during the meeting asked “Hey, Pepe! If they open this line soon, will I be able to visit Mum in Alicante more quickly and in more comfort?” “Certainly” replied The Governor. So she replied “Proceed immediately in making an order to remove the obstacles!”. Thus, the Governor ordered the Guardia Civil to remove the obstacles from the track. Before this meeting, Mr Kennedy had a train waiting in Huércal-Overa for a telegraph from Zurgena that the obstacles were removed and to travel with a notary public to Zurgena thus inaugurating the section and in the same action negating one of Loring's biggest actions against the Company. This infuriated Loring which resulted in the Governor being sent to live with his wife and mother-in-law in Alicante without ever travelling on the Murcia - Granada Railway.

Loring was being resistant to all suggestions from the company but eventually, he saw that Kennedy was behaving intelligently and cleverly for the company, so eventually he agreed to a meeting in London in December of 1901 whereby all problems were resolved.

MARÍN, CARRASCO AND FERNÁNDEZ

See also Lloret Baldó's text in El Boletín.

We begin the story of such asinine stupidity that it is hard to believe, except that it is documented.

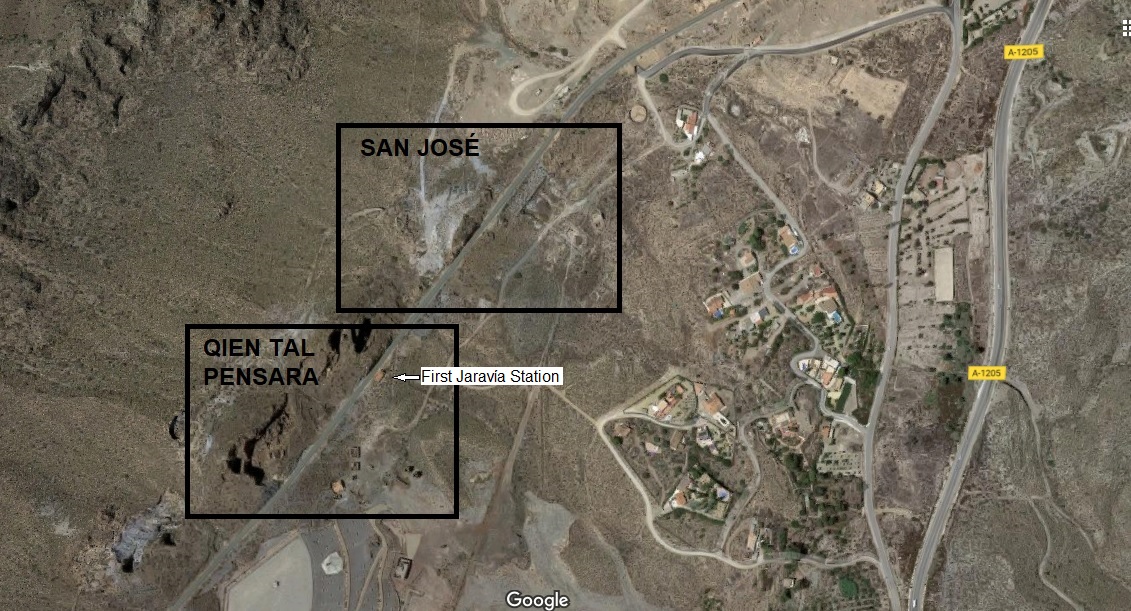

Alejandro Marín and Francisco Carrasco were mine owners in the area of Pilar de Jaravía at a time when the profitability of mining was very poor to zero. This meant that they had to store ore until a time when the price of ore on the World markets was sufficiently high that they could cover the costs of transporting it the four kilometres to San Juan de Los Terreros beach for hand-loading onto steamers. Before The GSSR, Marín hadn't exported more than 10,000 tons to the beaches of Los Terreros and Carrasco not even one single ton. For this reason, The GSSR chose the route that is the same as that of today so that Marín's mines such as Quien tal pensara and Carrasco's mines such as San José could load their ores directly onto the trains. For this purpose, the first Jaravía Station and the corresponding track was built subject to the Law of Expropriation, and which are the cause of this legal nonsense.

As a result of the forced expropriation of part of the mining territories of Quien tal pensara and San José, authorized by The Minister of Development in February 1889, with the object of running the line between Almendricos and Águilas, passing through Pilar de Jaravía, the presidents of the mining societies, Alejandro Marín and Francisco Carrasco, believing that their rights had been infringed, iniciated a process of claims which would mean the opening of a court case which would, over time, become a monster. Incredibly, they didn't seem to consider the incredible benefits that this would bring, possibly making them incredibly rich.

This all started in 1888, with the preliminary studies of the route, given that sufficient local and provincial authorities were involved in - according to the protagonists - a pile of irregularities at the time of complying with the requirements of the law in each case. In the first place, it seems that the Mayorship of Pulpí "failed to notify a sabiendas (being fully cognisant of)" the owners the act of expropriation as was their duty, under the pretext that they didn't know who they or their representatives were. They stated that the expropriation was going on behind their backs and claimed the amount of 33,666 pesetas recompense which was the estimate of the value of the land by the authorities. They were also required to present independent valuations so they contracted the Head Engineer of Mines for the Province of Almería, who calculated 1,765,236 pesetas for immediate payment, "and in addition, a guarantee of another two and a half million pesetas as a result of further damages which could also be caused by the establishment of a railway over the land of said mines, and that today cannot be estimated". It didn't work, as on the 11th February 1889 the governor stripped Marín and Carrasco of their lands and passed the ownership, via the Mayor of Pulpí, to the railway concessionary.

Both Marín and Carrasco, feeling that they were victims of an excessive abuse, placed a further appeal to the Ministry of Development. These complaints flew around the labyrinth of the Spanish legal system for some time. This undertaking didn't achieve the result intended, because - as is known - the work on the branch line continued without pause up to its conclusion in 1890.

However, a Royal Order of 22nd July 1894 by the Ministry rejected some of the pretentions formed by the representatives and the quantity surveyor of The GSSR, those pretentions that had been directed exclusively to take away importance and potential productivity in the expropriated zone with the intention of reducing the future indemnization of the old proprietors. The previous ones having been rejected, they started a new series of assesments that was inaugurated by the concessionary company of the railway and, for this, they assigned a surveyor who, after pertinent work in the country, evaluated the total indemnizable value of the workings of Quien tal pensara as 9,060 pesetas and San José as 19,605. Such estimates angered even more those that were the agitated minds of the damned, who didn't delay in rejecting in full the calculations that they judged to be cooked up and without foundation:

"Starting - the surveyor of the railway - principally in supporting the absence of lead ore below the iron in said mining concessions, had to close his eyes to the evidence, given that the ore is there, in view; erroneously interpreting certain assays performed on the ore, assays that which, skimping on the real profit per ton, they have been given extrordinary importance, determing the volume by whim of solid ore that is to be found in the zone of expropriation, taking the price of ore per ton from professional magazines of the market, whose prices differ considerably from the conditions of sale of our ores; and committing, at last, no few numerical errors in simple arithmetical sums, coming to the valuation that the profits of exploitation are 1.5 pesetas per ton".

On appreciating the above valuation as an inadmissable stupid document, the mining society representatives contracted the services of the engineer Fernando B. Villasante, who put to work with swiftness that the reduced deadlines required. After a consciencious study of the mines, volumetric measurement of the ores and the calculation of the potential productivity of the expropriated lands, he calculated that the amount indemizable should be in the region of 278,298 pesetas for Quien tal pensara and 195,493 pesetas for San José.

Such extreme differences caused such an insurmountable disagreement that the civil governor of Almería wanted to pass interest in the case, as was mandatory in these cases, to the 1o Instance Court in Vera. His first decision was to assign a third surveyor, the responsibility falling on a engineer for the district of Almería, Francisco Sáez Martínez. After the obligatory work on the affected lands, he released a report - vague and light, like those affected - in which he fixed the compensation for Quien tal pensara at 53,904 and that of San José at 67,394. This vagueness and lightness that was referred to by some miners was the result of some irregularities committed during the time of the meeting of the antecedents, of those that were disregarding contravening the Ley de Expropriation Forzosa. In the end, with the emphatic refusal of Marín and Carrasco, the governor of Almería accepted that estimate as the base of his Royal Decree of 15th October 1895, in which he recognised definitively the valuations of the third expert. The only one that could satisfy - according to his own opinion - the requirements of the mining societies was the recognition of the rights to the perception of their legal interests, the final assessment which was generated since the 11th February 1889 distorted and arbitrary - and the affected speak again - they were disposessed of their property. Against the part of the decree that they considered injurious to their interests, they returned to present a new appeal to the Minister of Development, fuelling again a conflicting case which showed a sheen of trying to prolong sine die (without assigning a day for a further hearing).

Just like they would demonstrate after the outcome of the events, the mentioned legal claims didn't have any effect, the least regarding the original pretentions of the mining societies, which called for compensation relating to the estimate provided by their expert. Then, in 1898; the director of works on the railway, Gustave Gillman, accompanied by Miguel Lloret Baldó, Commercial Manager of The GSSR, and in the presence of the Mayor of Pulpí paid Alejandro Marín 80,000 pesetas and Franciso Carrasco 30,000 for the alleged damages caused by the expropriation of the mining land during the construction of the railway. Lloret complained acidly that he considered it ignoble behaviour by the complainants, an abuse in every rule against his company, that which, in weight of the intentions of improving progress for the area, in view of which, he saw it as a disgrace to pay the compensation - according to his opinion - totally unjust, and all with the consent of the administration:

"The Company, as previously stated, established Pilar de Jaravía Station very close to the mines, one could say within their boundaries, with the exclusive object of giving the best facilities for the transport of ores, but the proprietors didn't recognize the benefits, on the contrary, took to the refuge of the Law of Expropriation, they abused the company and extracted the compensation for whose happy result we tell the story."

And more, the same employee reproached the railway company that hadn't reacted to the unjust demands of the claimants with any method of negatively influencing the mining interests and so they were able to capitalize on their claims. He wrote that he could have modified the location of the station that ended up in Jaravía, placing it before the Puerto de Los Peines or moving it 3 or 4 kilometres in the direction of águilas. In the first case, one could have offered a reason as Guazamara had been offered a service along with the mines in that area, and in addition, due to the construction of a road that passed along the west hillside of the Sierra Almagrera, they reduced the distance from the rich extractions of iron and lead having been established there to a new station in another site for these ores. The second option, which placed the station in el Cocón, would favour the village of Los Arejos and, furthermore regarding the transport of ores from Jaravía, it could have facilitated that which was produced in other neighbouring areas between Águilas and Pulpí. And concluding with apreciable indignation:

"....therefore, as we have seen, that the distance of the ores meant an increase in the costs of carrying the ore in wheelbarrows four kilometres to the loading point, Marín and Carrasco begged us to move the station, the one that we had had to move due to certain conditions and they were denied this and got their just rewards".

And to reinforce even more this sense of injustice and abuse that the company was tolerating, Lloret alludes to the benefits that the station of Jaravía has deprived of Marín and Carrasco.

"Don't doubt, then, in resorting to the company files, when one reflects that, from the inauguration of the line up until 1917, there were transported 270,000 tons of calcinated and uncalcinated iron from the mines of Marín and Carrasco, an amount that contrasts informatively with the amount carried before the railway with Marin not even carrying 10,000 tons and Carrascco not even loading one ton. So regarding these profits, according to my calculations the profit at 4 or 5 pesetas per ton accumulated to more than a million pesetas thanks to the construction of the railway and to those one must add 110,000 due to the Law of Expropriation while the Company, in the transport of 270,000 tons, has gained hardly 120,000 pesetas, from which one can deduct 110,000 pesetas due to the claim which only comes to 10,000 pesetas in the 27 years since the railway started to function."

These problems dissuaded other British capitalists from investing in Spain once the story was heard there and so, Messers Marín and Carrasco ended up having a profound negative affect on the Spanish economy.